My opinionated scaffolding for modern Python projects

Python is a pragmatic programming language and asks for very little to get started. A text file with valid code, conventionally ending in .py and forming a “module” in Python jargon, is already a small program (a script); we run it with python <file> and we are done. But when that simple piece of code needs to grow into more files or deserves to be distributed —maybe because it will be a dependency of another project or simply because someone else might benefit— then it needs some structure and metadata.

That is not exclusive to Python: when you start a software project there is always a basic set of files and structures that serve as a starting point; the minimum set of files, folders, configs, and "basic" code you need when you want to share code as an app or library: the project boilerplate. The boilerplate does not define logic, but it does lay the technical foundation—often based on conventions and sometimes on personal taste—on which everything else will be built.

This article details the decisions I made for the template and automated scaffolding I created for my projects, based on Copier.

In short:

- 🐍 Modern Python package (3.12+)

- 📦 Build and dependency management with uv, split by groups (dev/qa/docs)

- 🧹 Linting and formatting via Ruff with a broad set of rules enabled

- ✅ Type checking via ty

- 🧪 Tests with pytest, coverage.py and extensions

- 📚 Docs with Sphinx, MyST and a few extensions, deployed to GitHub Pages

- 🤖 GitHub project creation automated through GitHub CLI

- ⚙️ CI workflow on GitHub Actions

- 🚀 Automated releases via Trusted Publishing

- 🧠 Sensible defaults via introspection to minimize answers in the initial questionnaire

- 🛠️ Makefile with shortcuts for common tasks

- 📄 Generation of generic docs such as LICENSE/CODE_OF_CONDUCT/AGENTS.md, etc.

- 🌀 Initial setup of the development environment and git repo

- ♻️ Projects updatable with

copier update

And a bunch more details I am surely forgetting.

If you want to try it, it is at mgaitan/python-package-copier-template and you can spin up a project like this:

uvx --with=copier-template-extensions copier copy --trust "gh:mgaitan/python-package-copier-template" /path/to/your/new/project

Minimal Bootstrapping in Python

A minimal boilerplate for a current Python project—installable and distributable—can be created with [uv init --package](https://docs.astral.sh/uv/concepts/projects/init/#packaged-applications) (heavily inspired by cargo init for Rust):

$ uv init demo-project --package Initialized project `demo-project` at `/home/tin/lab/demo-project`

That yields:

$ tree demo-project/ demo-project/ ├── pyproject.toml ├── README.md └── src └── demo_project └── __init__.py 3 directories, 3 files $ cat demo-project/pyproject.toml [project] name = "demo-project" version = "0.1.0" description = "Add your description here" readme = "README.md" authors = [ { name = "Martín Gaitán", email = "gaitan@gmail.com" } ] requires-python = ">=3.14" dependencies = [] [project.scripts] demo-project = "demo_project:main" [build-system] requires = ["uv_build>=0.9.9,<0.10.0"] build-backend = "uv_build"

This boilerplate declares demo-project as a CLI, mapped to a main function that is just a placeholder for your code.

$ cd demo-project/ $ cat src/demo_project/__init__.py def main() -> None: print("Hello from demo-project!") $ uv run demo-project Using CPython 3.14.0 Creating virtual environment at: .venv Installed 1 package in 6ms Hello from demo-project!

If you install your program with uv tool install ., you can run demo-project from any directory.

But again, this is the bare minimum. Any respectable project defines unit tests (and how to run them), configures linters with style rules, ideally has docs, declares auxiliary dev dependencies, has a CI workflow, is versioned with git, and even includes badges in the README header. Which test framework do we use? How do we generate docs? Will the project use a src/ layout or flat?

That is a lot of decisions to make (which can change over time) and a lot of work to implement by hand. Even more so when we get used to doing things one way and want the same setup across projects.

This is where the concept of scaffolding comes in: generating boilerplate from templates that you can edit centrally. The most generic and trivial way to do this is to mark a repository on GitHub as a “template” so that when you start a project you begin from the template repo’s HEAD state instead of an empty repo (but without forking it).

But starting a project is not just creating boilerplate; it is also preparing the dev environment, initializing the repo, creating the project on GitHub and maybe pushing an initial commit, checking that the package name you chose is not already taken, etc. All that project bootstrapping also implies repetitive, time-consuming tasks. Let’s automate them!

In Python, the best-known scaffolding + bootstrapping tool is cookiecutter. Although it is written in Python (templates are defined with Jinja), it is not limited to Python projects—there are cookiecutter templates for almost anything!

cookiecutter is great, but it handles the initial bootstrapping only. What happens when conventions change or we adopt a new preference? For instance, I used Nose long ago as a testing framework and runner, and now I use pytest. Python itself replaced setup.py with pyproject.toml, and the canonical default builder moved from setuptools to

And so on.

Again, if we have many projects, changing the same thing in many places is boring and repetitive work.

That is why my template is based on Copier. In many respects it is similar to cookiecutter (there is a comparison table), but it also supports updates to generated projects, meaning any project created from the template can apply new features with a single command.

My body template, my call

The template assumes Python 3.12+ with a src/ layout and unified config in pyproject.toml. The build backend is uv_build, which is more than enough for “pure Python” projects (no compiled extensions). It declares an (optional) entrypoint script using argparse and includes --version and --help.

Obviously I use uv to manage dependencies and the environment. While the initial project does not declare runtime dependencies (no “domain logic” yet 1), I do declare several dependency-groups, a mechanism defined in PEP 735 that organizes dependencies into sets by purpose—e.g., test, docs, etc.—avoiding everything being lumped into main dependencies and making partial installs easier depending on environment or task. This lets us, for example, install only doc dependencies when building docs (saving precious CI time), or run QA with ruff without installing dev-only tools like ipdb. When uv installs or syncs dependencies (e.g., via uv sync) it looks for the "dev" group by default; in my template that is a meta-group that includes test, QA, and other extras.

ruff, as mentioned, is the canonical linter right now. From the same creators of uv (also written in Rust), its performance is uncanny. It covers linting (replacing flake8, isort, and dozens of plugins) and formatting (replacing the trailblazing black) with a 120-character line limit (the 79 recommended in PEP 8 feel too short on today’s screens) and a broad set of rules enabled. Most rules have autofix (and when they do not, the agents take care of it), so it keeps a consistent Pythonic style that minimizes bugs. I might enable even more rules later: if it is free, automatic, and fast, I want them all.

The package includes inline typing and ships the py.typed marker (PEP 561). Type checks run with ty, another Astral tool that is still alpha but already usable for new projects.

The unit testing stack uses the de facto standard pytest and coverage.py via pytest-cov (configured with a 100% threshold), plus plugins for generic mocks and dates. While we could use unittest.mock from the stdlib, I like the mocker fixture because it does not force context managers for patching. As the Zen says, “Flat is better than nested.”

For a brand-new project with undefined scope there may not be much to document (maybe the README is enough), but having the scaffolding ready makes it trivial once there is something to write. So the template includes a docs/ folder with the starter structure. I could have used MkDocs, which is increasingly popular, but I stuck to classic Sphinx using MyST parser to write in Markdown (I used to like reStructuredText but I know a champion when I see one). I include a couple of my Sphinx extensions already configured: sphinx-mermaid for diagrams and richterm to embed "captures".

After creating the initial code, it run a few automatic tasks. For example, the first uv sync installs dev dependencies, and a first commit is created with git. Then, if GitHub CLI is installed (highly recommended), the repo is created on GitHub, pushed, and the first workflow is launched without manual steps.

The generated tests and the QA checks (ruff/ty) run in a CI workflow triggered on every push or PR, running tests on a Python version matrix. The tools are configured to emit errors or warnings as GitHub annotations so you can navigate them in context.

Another workflow handles releases. The typical release flow starts with make bump + make release (bump the version, commit, and start a GitHub release). The workflow detects that event, builds wheels (via uv build) and attaches them to the GitHub release, and also uses Trusted Publishing to upload the new version directly to PyPI. It also builds and updates the docs served from GitHub Pages (if the repo is public).

The traditional way to upload packages to PyPI involved tools like twine that require a token or user/password. Trusted Publishing, instead, manages authentication dynamically (using OIDC), so there are no secrets to manage (or rotate). Because PyPI’s API still does not expose endpoints for this registration, the only manual step—done once—is to register the package and the workflow. In my case the workflow is cd.yml and I leave the environment blank.

When you run Copier with a template, it launches a questionnaire: package name, author, GitHub user, that sort of thing. I automated whatever I could to provide sensible defaults so you answer as little as possible. For example, the project name is inferred from the target directory, author name/email come from git, and the GitHub user from the API via GitHub CLI.

A lesson learned: many times I came up with a project name only to realize at publish time that it was taken (my recent textual-tetris was originally “textris,” but someone beat me to it). So the wizard checks whether the package name is available on PyPI with a simple web query and, if it is taken, suggests a suffix.

In the generated project I defined a Makefile with shortcuts for “day-to-day.” For example, if you want to build the docs locally as epub, you do not need to remember the Sphinx arguments; just run make docs-epub (there is also a make help). While there are newer tools like just or mise (there is also invoke but I abhor it), the 50-year-old make is ubiquitous and sufficient for these humble needs. Targets like qa, test, docs, and release wrap long commands and keep a uniform interface for recurring tasks.

Alongside code, the template generates the usual copy-paste documents like LICENSE and CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md (from the Contributor Covenant). I also include an AGENTS.md with basic instructions so code agents understand the working context and preferences.

Updates with Copier

Perhaps Copier’s most interesting feature is that it can update projects that already exist, because any self-respecting programmer has principles—but changes them over time.

I recommend the interview with Jairo Llopis (one of Copier’s maintainers) in this podcast where he describes Copier as a “project life cycle management tool,” as opposed to a traditional scaffolding tool.

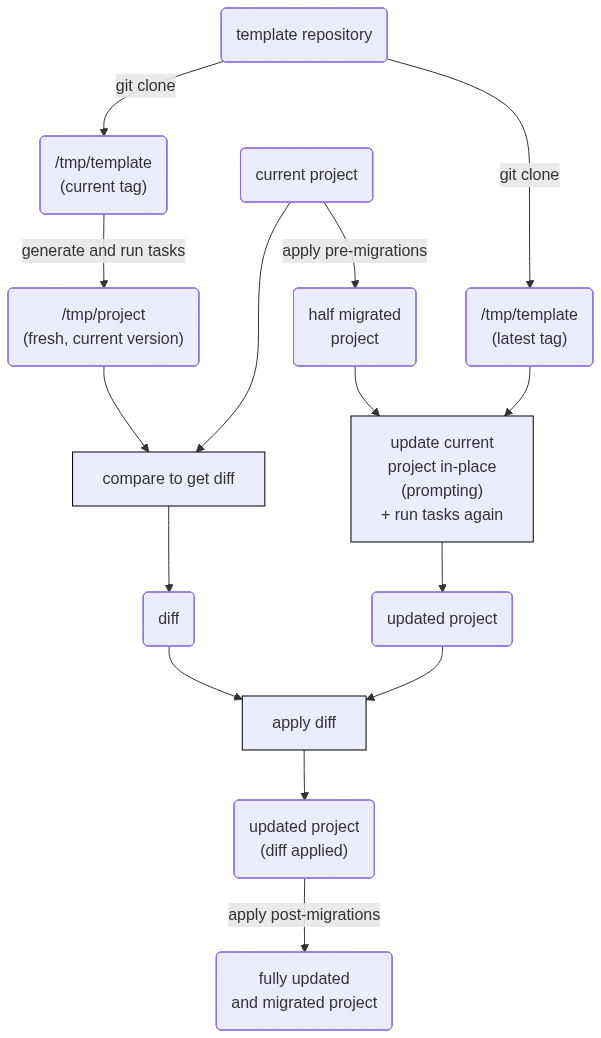

When everything is ready in the generated project, Copier leaves a small .copier-answers.yml file with metadata about the template used and the variables (the answers to the initial questionnaire). If there are updates in the template (by default it looks for tags), running uvx copier update is enough to apply them (or at least try) to the project, even if the project has changed.

The mechanism is not trivial: it involves extracting and applying diffs (remember, the template and the project are completely separate repos with no shared history). It is summarized in this diagram from the docs:

No Silver Bullet

I have been using Python for many years and have seen conventions and tools change. Packaging in particular has been a long-standing hassle that other tech communities have mocked. Fortunately, we now have robust standards, and the arrival of uv seems to have settled the debate.

Still, as seen above, there are many decisions here that I may revisit over time. If you agree with many of them but not all, and editing directly in the generated project is not enough (maybe you do not care about Makefile because you use Windows—delete the file and move on), then fork the template and make your own flavor. That is exactly what I did: my template started as a fork of this one.

Hope it helps and long live the Free Software!

-

Just as in recent years we have been revisiting and politicizing language in our industry—trying to avoid sexist, enslaving, or militaristic terms—we should also stop seeing software purely in capitalist terms. I am looking at you, “business logic.” ↩

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus