textual-tetris, a Tetris in the terminal

Since I remain unemployed while prioritizing my search for mental health, I spend my nerdy time on two worthwhile tasks:

- Collaborating with organizations that need technological solutions but do not have the budget to compete in the market for my skills.

- The one relevant to this post: learning new things by implementing old ideas from the permanent

TO DOlist I keep here, the ones I almost never found time for.

This time I wanted to learn a bit about Textual (the elder sibling of rich), an excellent Python framework for building text-based users interfaces.

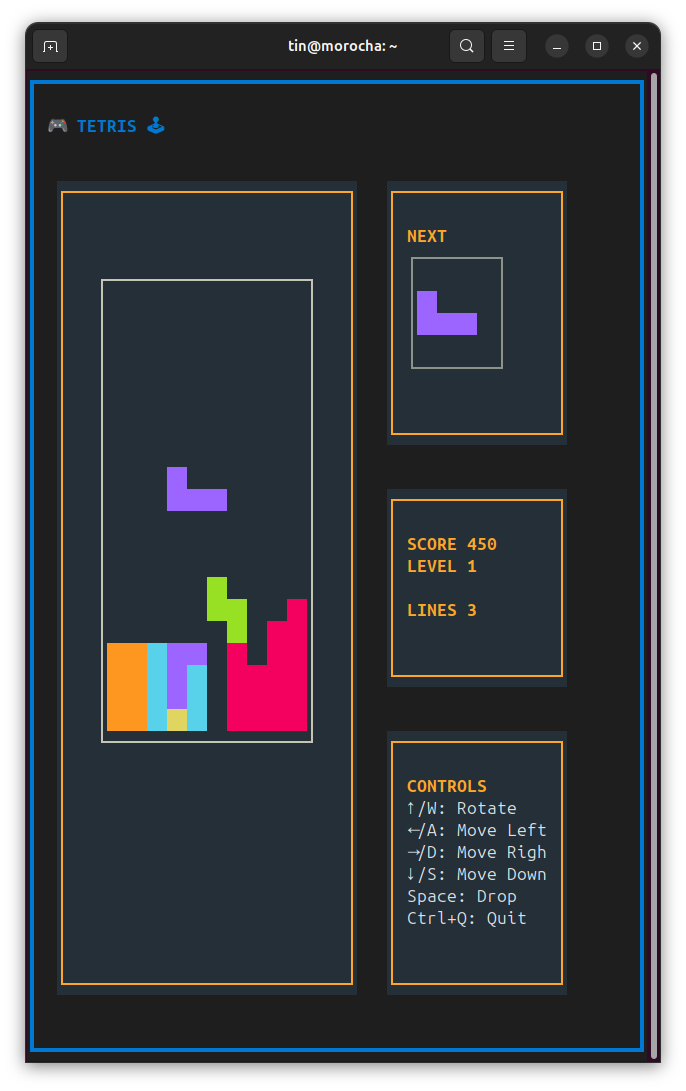

And while I was at it, I learned how to make a Tetris clone that is pretty decent to play, does not look that ugly, and currently sits at under 600 lines of Python code, comments included. It looks like this:

But a taste is worth more than a thousand screenshots: open a terminal and, if you have uv installed (you should!), run:

uvx textual-tetris

And you are already playing Tetris!

A walk through my implementation

Tetris is not just any game. It is a pop culture icon, a product with geopolitical weight (do not miss this article by Tomás Aguerre on the topic --in spanish--), and an obsessive passion for the people who play it and program it.

There are thousands of versions in dozens of programming languages. From a code golf version in JavaScript that fits in only 351 bytes, one in assembly that boots as an operating system, and even one implemented inside a PDF file!.

Mine is much more classic, but it has a few implementation details I want to point out.

For example, I borrowed Ole Martin Bjørndalen's idea of encoding tetrominoes in all their possible orientations as a set of hexadecimal coordinates inside a 4x4 grid.

I recorded a short video to explain it:

In the code it looks like this:

PIECES = { "O": {"color": "yellow", "codes": ["56a9", "6a95", "a956", "956a"]}, "I": {"color": "cyan", "codes": ["4567", "26ae", "ba98", "d951"]}, # ... } class TetrisPiece: ... @property def shape(self) -> list(tuple[int, int]): coords = [] for char in self.code: value = int(char, 16) y, x = divmod(value, 4) coords.append((x, y)) return coords

That property gives us the relative coordinates of the piece for the rotation described by self.code. Later we add those to the piece's x, y position relative to the board to compute the absolute position of the cells to draw. If these coordinates fit within the board dimensions, the cell changes from showing two blank spaces to two "█" characters (the full block char) with the piece color.

for board_x, board_y in self.current_piece.blocks: if 0 <= board_x < self.board_width and 0 <= board_y < self.board_height: display_board[board_y][board_x] = self.current_piece.color for row in display_board: for cell in row: if cell == 0: text.append(" ") else: text.append("██", style=f"bold {cell}")

Rotating a piece basically means swapping the current code for the next one and looping back to the beginning once you run out (what is known as a round-robin).

Originally I kept track of a rotation index computed with modulo arithmetic.

self.rotation = (self.rotation + 1) % len(self.codes)

Later I changed (simplified?) it to use collections.deque, which already has rotation methods.

class TetrisPiece: def __init__(self, piece_type=None): ... self.codes = deque(PIECES[piece_type]["codes"]) @property def code(self): return self.codes[0] def rotate(self): self.codes.rotate(-1) def undo_rotate(self): self.codes.rotate(1)

undo_rotate is needed because when the board receives the command to rotate the current piece, it checks for collisions before rendering, and if there is one, the rotation must be reverted. For the player, this is the same as "you cannot rotate here":

def rotate_piece(self): """Rotate the current piece""" self.current_piece.rotate() # Check if rotation causes collision if self.check_collision(): self.current_piece.undo_rotate() return False self.update_display() return True

The same try/revert-on-collision criteria applies to movement. Here is move_piece:

def move_piece(self, dx, dy): old_x, old_y = self.current_piece.x, self.current_piece.y self.current_piece.x += dx self.current_piece.y += dy if self.check_collision(): self.current_piece.x, self.current_piece.y = old_x, old_y if dy > 0: self.lock_piece() return False self.update_display() return True

But what counts as a collision? Discrete geometry:

def check_collision(self): for board_x, board_y in self.current_piece.blocks: if board_x < 0 or board_x >= self.board_width or board_y >= self.board_height: return True if board_y >= 0 and self.board[board_y][board_x] != 0: return True return False

When moving down (dy > 0), if we hit something, lock_piece is called: it locks the colors into the grid, clears full lines, and notifies the App. That answers the classic "why can't I keep going down?" Because the function tried the move and it collided with a wall or an already locked block.

Widgets, bindings, and Textual magic

A Textual app is made up of widgets (buttons, inputs, options, etc.) that can be grouped into Container instances. Every widget and container can be associated with a (pseudo) CSS style.

The composition for this Tetris is pretty self-explanatory:

def compose(self) -> ComposeResult: with Container(id="game-container"): yield Label("🎮 TETRIS 🕹", id="title") with Horizontal(): with Container(id="board-container"): yield TetrisBoard(id="board") yield Static("GAME OVER\nPress R to restart", id="game-over-overlay") with Vertical(id="sidebar"): with Container(id="next-piece-container"): yield NextPieceWidget(id="next-piece") with Container(id="score-container"): yield ScoreWidget(id="score-widget") with Container(id="controls"): yield Label("CONTROLS", classes="section-title") yield Label("↑/W: Rotate") yield Label("←/A: Move Left") yield Label("→/D: Move Right") yield Label("↓/S: Move Down") yield Label("Space: Drop") yield Label("Ctrl+Q: Quit")

All the custom widgets I defined—TetrisBoard, NextPieceWidget, and ScoreWidget—inherit from Static, the most basic, non-reactive widget, but one that can obviously be re-rendered as many times as needed to update its contents.

Those updates get triggered by various events, in this case keyboard input and a timer that handles automatic falling (Textual also supports mouse events). The bridge between events and logic lives in TetrisApp.BINDINGS:

BINDINGS = ( ("left,a", "move_left", "Move Left"), ("right,d", "move_right", "Move Right"), ("down,s", "move_down", "Move Down"), ("up,w", "rotate", "Rotate"), ("space", "hard_drop", "Drop"), ... )

Each binding maps key combinations to action_* methods. When Textual detects the key event, it calls action_move_left, action_hard_drop, etc. An excellent developer-facing API if you ask me!

And there is a neat trick: when you lose, beyond showing the "Game over" overlay (which actually always exists but stays hidden), the method in charge also disables several bindings dynamically, so you cannot move anymore. Unplugging events from actions like this keeps the methods clean, without littering them with checks such as if not self.game_over: ....

By the way, Textual's documentation is incredibly good. I recommend reading it even if you do not yet have a project in mind.

Rack up the points!

When a piece can no longer fall (because a manual or automatic downward movement collides), the on_piece_locked method gets called.

if self.check_collision(): # Revert move self.current_piece.x, self.current_piece.y = old_x, old_y # If we were moving down, lock the piece in place if dy > 0: self.lock_piece()

This method adds points, checks whether you level up, and in turn increases the falling speed.

line_score = {1: 100, 2: 300, 3: 500, 4: 800}.get(cleared_lines, cleared_lines * 200) self.score += line_score * self.level if cleared_lines else 10 self.lines_cleared += cleared_lines self.level = max(1, 1 + self.lines_cleared // self.lines_per_level)

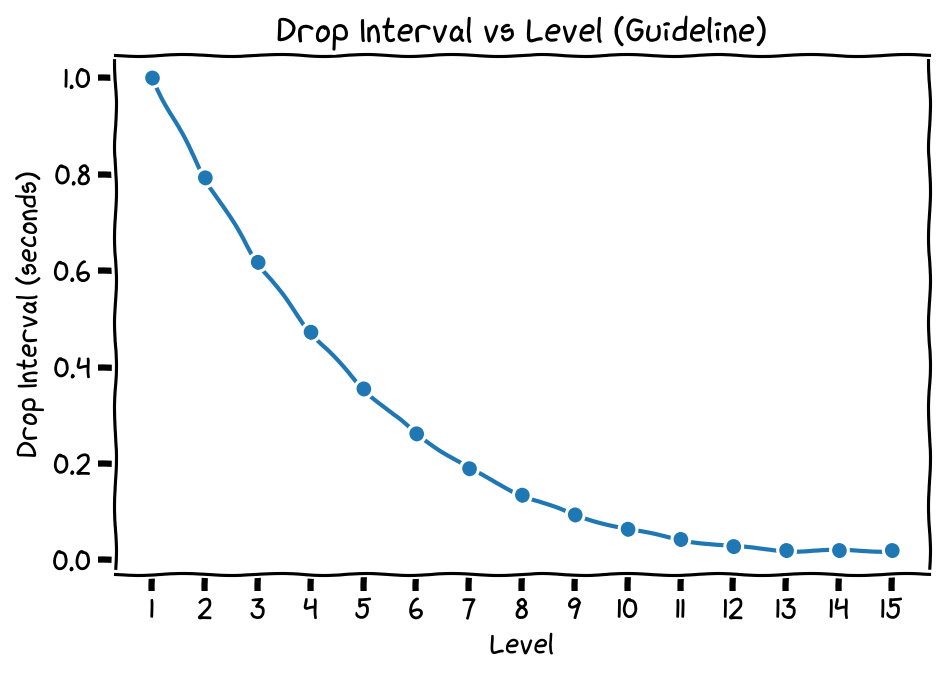

The duration of the pause between every automatic drop step (a.k.a. the "gravity" speed) is an inverse exponential function of the level.

Plotted, it looks like this:

Where did I get that outlandish formula? From the official Tetris design guideline, of course.

If you want every recommendation from that guideline for your own Tetris clone, there is a Python library that implements it seriously.

What's still pending?

The UI is kind of mediocre, let's be honest. Textual is amazing, but arranging things on screen still requires knowing some CSS, and we Python folks are not famous for that. LLMs do not help much either.

The code could probably be tidied up too. For example, there is some duplicated logic between the board rendering and the next-piece widget.

Restarting a game is a bit crude (it spawns a new process!). There is no pause action. And above all, it still lacks the support for two (or more!) players at the same time —the strongest request from my most skilled user, my 10-year-old daughter Ema.

I would love to hear your comments, suggestions, and pull requests!

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus